By: Razi Syed, Lisa Setyon and Jennifer Cohen

As Homelessness Reaches Record Highs, Families Say They Struggle to Get Permanent Shelter Placements

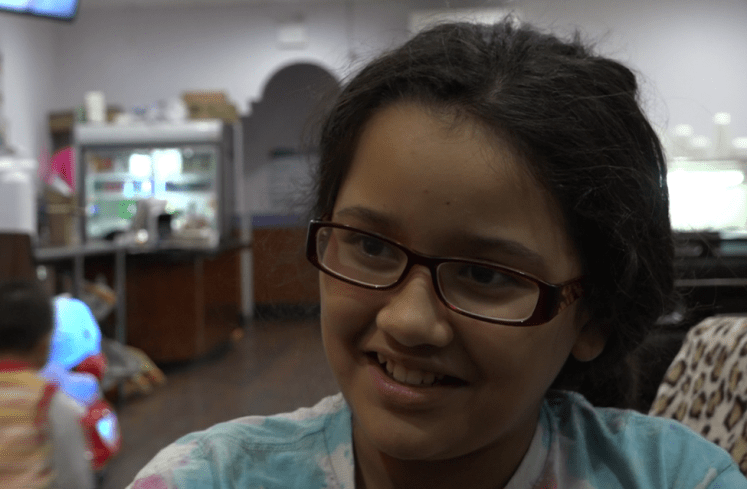

Monica Espinosa is only 10 but she has seen first-hand how the city treats homeless children like her.

When her teacher told her one recent October morning that she had to go home, she immediately knew why and what to expect. The fourth grader, who has been living with her family in a Brooklyn shelter for the past month, anticipated another missed day of school and another lengthy trip to the Bronx, the site of the city’s Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing center (PATH), the city’s only intake center for homeless families seeking shelter placement. And endless waiting while her mom tried to negotiate the city’s homeless intake system.

“They start calling me and I got sad because they said it was about PATH,” said the fourth grader. “Every time we have to leave it’s because of PATH.”

Monica, who is one of the nearly 24,000 homeless children in New York City, whose families are often required to apply multiples times for assistance and are repeatedly denied shelter. She spends the hours at PATH, a gleaming office building in the South Bronx, reading and practicing her spelling. Since September, Monica, her 8- and 7-year-old siblings and parents have been granted temporary stays at a Brooklyn shelter while they make repeated trips to the intake center to reapply for a permanent shelter placement, said 29-year-old Juan Espinosa, Monica’s father. While going through the arduous application process, which regularly requires all-day stays at the PATH building, Espinosa has been the stay-at-home caretaker for his three children while his wife works at a gas station in the Bronx. A three-month investigation of the city’s intake system for family shelters as found:

- The lives of children – the city’s most vulnerable homeless population – are often needlessly disrupted as their parents attempt to prove to the city they are, indeed, homeless or are rejected due to technicalities in their application

- Homeless children lose days, and sometimes weeks, of schooling while parents return over and over again to the city’s only intake center for homeless families in the Bronx

- Often, after spending the entire day at the intake center, the families have yet to finish the application process and are sent to a hotel, only to return a few hours later to wait and speak with a PATH worker

- Some families and children spend years in the shelter system and the children bear the stigma of being one of the 24,000 homeless children in the city’s school system

The New York City Department of Homeless Services did not reply to multiple requests for an interview.

Monica Espinosa, 10, has been living in a Brooklyn shelter with her 8-year-old brother, 7-year-old sister and parents since September. The Espinosa family has struggled to get permanent shelter despite their multiple applications at the city’s shelter intake center for families in the Bronx.

From July to December 2016, the number of families with children that had to apply multiple times for shelter jumped from 37.5 percent to 44.9 percent, according to the coalition’s 2017 report on the city’s homeless problem, which used data from the NYC Department of Homeless Services.

New York City’s homeless shelters have been operating at near-capacity for months, with the Department of Homeless Services reporting 60,305 people in homeless shelters as of Oct. 17. Those include more than 12,907 families with 23,132 children. On Oct. 17th alone, 144 families sought shelter at PATH.

In response to the overwhelming need for space to shelter the homeless, the city has also expanded the longtime city practice of housing people in commercial hotel rooms — some of which have costed the city upwards of $600 a night, according to city comptroller Scott Stringer. From Nov. 1, 2015 and Oct. 31, 2016, DHS made 425,000 hotel room booking at a cost of $72.9 million, according to an audit from the comptroller’s office. During that period, the number of hotel rooms booked by DHS jumped from 324 to 2,069 – an increase of 540 percent.

On a Saturday afternoon in early October, Kariyma Quashie, stood outside of the PATH intake center for homeless families in the Bronx with her 11-year-old daughter, Kefira. Quashie was gearing up to spend the third night in a row in her friend’s van after city officials determined for the third time she was ineligible for shelter, saying she hadn’t demonstrated she didn’t have elsewhere to stay.

Quashie was at PATH that afternoon to bring a notarized letter saying she was unable to stay at her aunt’s apartment. After entering the shelter system in September, she was granted two 10-day temporary stays until she was told she was ineligible for shelter and would not be given assistance while she applied again. For three nights Quashie said she slept in her friend’s van, while sneaking her daughter into a neighboring shelter, where another friend was residing.

“It’s been very stressful,” she said. She was wearing an olive green jacket, baseball cap and had her hair in two braids. As she spoke, she veered between desperate and angry.

“I’ve had suicidal thoughts to just end it all because of the fact that I work hard, I pay my tax dollars. All I’m asking for is temporary housing so I can go about to find an apartment so me and my daughter can live somewhere.”

Quashie added she was afraid to keep missing work, for PATH visits because she was still in a probationary period at her job as a teacher’s aide for children with special needs.

“At PATH, it’s an all day situation,” Quashie said. “If I come after 12 p.m., I’m going to be sent to an overnight then I have to miss work and my daughter has to miss school. So I’m trying preventative ways so we can get a placement before the night is out so she can go to school as a regular normal child without interruption to her education.”

Quashie’s daughter, Kefira, 11, was most upset about missing school. “Plenty of work I’m missing out, and I’m not happy about that,” she said. “I don’t want to be the person that misses out on school and everything.”

After seeking assistance from the office of Congressman Adriano Espaillat (D-NY), Quashie said she was finally given another conditional 10-day placement so she could apply again.

*************

Kathryn Kliff, a staff attorney at Legal Aid Society, said Quashie’s situation — where she was not provided any shelter while she appealed the decision — was not unique. Kliff represents families that SHE SAYS have been erroneously denied shelter by PATH.

Families reapplying because of their application being ruled incomplete are granted 10-day shelter stays while they reapply; families reapplying because they were found to have another location they could reside, like Quashie, are not provided any shelter, said Kliff, who represents 40 to 60 families each week.

Since November 2016, when the city modified a directive which determined eligibility for family shelter, families like Quashie’s have had to prove they are unable to live elsewhere before provided with shelter. The problem with the otherwise reasonable rule, according to Kliff, is that administrators at PATH are often unwilling to investigate whether or not families applying have elsewhere to stay.

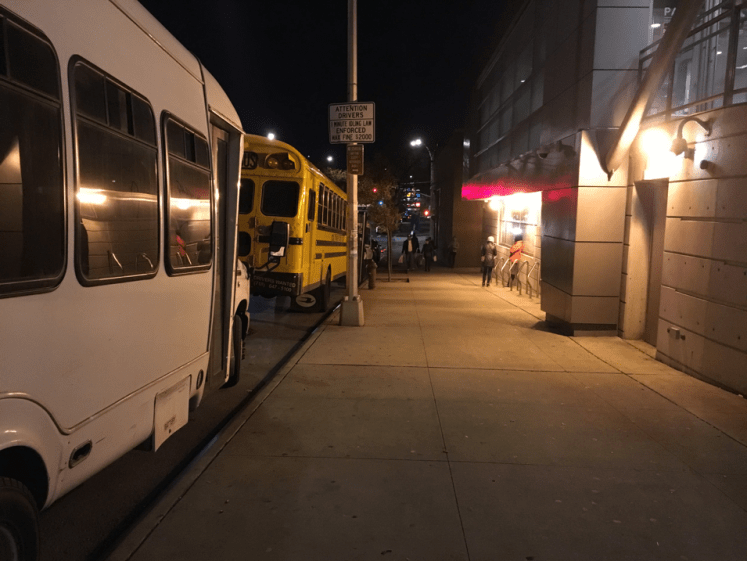

The Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) building in the South Bronx is the only intake center for homeless families in all of New York City.

The lack of investigation into why a family is seeking shelter from the city is an urgent problem with the intake system, Kliff said.

“Oftentimes, I meet clients and within an hour, within half an hour, within 15 minutes — I get why they can’t go back,” Kliff said. “I think a lot of times the staff at PATH is so overburdened and there are so many families coming through that they don’t really take the time to uncover the ‘why.’”

Kliff adds that workers at PATH will not always listen to what her clients are saying.

“Unfortunately, when clients tell PATH workers something, that doesn’t mean the worker is going to believe them but where as if me, the lawyer tells them something, suddenly we get a different response,” she said. “That’s a pretty disturbing dynamic but it happens everyday.”

While the city revised the eligibility requirements for families out of the belief that people were seeking shelter when they really didn’t need it, Kliff said she doubts that a large number of families seeking shelter have a place to stay elsewhere.

“Bloomberg used to say that he could take his private jet, take a private limo, go to 30th Street and get a bed,” Kliff said. “And while he is correct, in the single system, he could do that, we’ve yet to see client of that background ever attempt to go to shelter or want to, for that matter.

“In the family system — I would urge anyone who thinks people are flooding to our wonderful shelter system to sit through the process because it’s miserable.”

The application process, which DHS estimates takes nine to 12 hours but often is much longer, has families cooped up in plastic chairs for hours while they await for their names to be called, going to different waiting areas on each floor of PATH as requested of them. During a visit to Path in October, parents were seen holding their children in their laps, or watching over bored children, preventing them from running around the waiting area. Other children sat on the floor and played.

Roughly two-thirds of families are found ineligible the first time the apply meaning they have to start the whole process over, Kliff said. “That means missing work, missing school, missing jobs, missing medical appointments.”

When families are at PATH still going through the application process, the city utilizes yellow school buses to ferry homeless families to hotels around the city. Around 11:30 p.m. during a day in early October, families were seen loading strollers and bags of their belongings onto a school bus in preparation for being driven to a hotel somewhere in the city for the night. Early morning, they families will be bussed back to finish the application process.

Sheilah, 33, who requested her last name not be used, was at PATH on a mid-November evening after her shelter in Harlem told her she needed to leave for not making the facility’s curfew for the past two days – a charge that Sheilah disputes. She was with her three children – aged 14, 12 and 8 – and waiting to get sent to an overnight hotel until she can see an intake worker the next morning.

A school bus sits outside of the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) building on a late night in November 2017. Families who haven’t seen an intake worker by the end of the day are put on a school bus and transported to a hotel for a few hours before they arrive back at PATH and continue the waiting process.

“It’s like a runaround,” Sheilah said. “When you come here, it makes you feel like giving up.”

Sheilah’s daughter Dona, 12, said she was especially unhappy that she was going to miss the next day of school.

“I felt frustrated – I thought today was going to be a normal day but everything turned out different,” the fifth-grader said. “I’ve been here multiple times and I’m tired of coming back here.”

Dona added that she hasn’t shared her experience with any friends at her school, P.S. 194 in Harlem, because she was worried that they might pick on her because of her family’s situation.

Brittany Torres, 18, was sitting in front of PATH with her two toddlers this October waiting for her appointment. Torres said she and her mother applied for shelter several times before they were finally found eligible for shelter because PATH workers kept insisting they could stay with family members, whom Torres said didn’t live in the New York-area.

The most common reason for being denied shelter is failure to provide a full verifiable accounting of where the applicant was for two years prior to seeking shelter, which can be very difficult for homeless families, said Giselle Routhier, policy director at the Coalition for the Homeless and author of the nonprofit’s 2017 report.

Families must prove where every family member was for the two year prior to seeking shelter, Routhier said, which can be difficult for families bouncing around from friends and family members or who have experienced street homelessness.

They will find you ineligible if you miss two days of proving where you were, Routhier said.

*************

On an evening in early October 2017, 24-year-old Jeane, who asked that her last name not be revealed because she didn’t want to identify her family as homeless, was at the intake center with her 2-year-old son to seek assistance over a half-dozen times during the previous several months.

With dark circles around her eyes from lack of sleep and exasperation evident in her voice, she explained she had been living with her mother and family in a one-bedroom apartment as was told she couldn’t live there anymore, because of a landlord complaint about the number of people in the apartment.

Dona, 12, stands in front of the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) building, where homeless families are required to go for the shelter intake process.

“I’ve been in Queens, they put me in a place in Harlem — but that’s only for 10 days,” Jeane said. “They told me I have to go back my mother’s house but she won’t let me back. They’re trying to force my mom to let me live there, which is not feasible.”

Since January 2017, Jeane said she had bounced around from 10-day stays at family shelters and short periods of staying with friends. “I’ve exhausted all my options,” she said.

Chantell Smith, a mother of four children, said she was found ineligible four times in a row.

“I came into find out that I didn’t make it in at 9 am for my counsel with their team, they closed my case,” Smith said, standing across the street from PATH on a late October night. The meeting was scheduled at a time she couldn’t come because of her work schedule and when she got in that day, her case had been closed and she had to reapply.

For those that do get shelter, more than half the time children are placed in shelters located far from their schools, according Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 2017 management report.

The shelter capacity issues have resulted in fewer and fewer children being placed near their schools. According to the mayor’s 2017 management report, families are housed near the school of the youngest child only around 43.7 percent of the time — down from 95.1 percent of the time in 2005.

The proximity of their shelter placement to the school has a direct correlation to that child’s school attendance and performance, said Routhier.

According to state data released this month, over 110,000 NYC student experienced homeless at some point during the 2016-17 school year. Students experiencing homelessness are more likely to experience chronic absenteeism and have a 54 percent graduation rate compared to 77 percent for non-homeless students, according to a 2017 report by the NYC-based Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

Serenity, 11, who lives in a homeless shelter on the Upper West Side starts her commute at 6:30 a.m. each morning for the one and a half-hour commute make it to her school in the Bronx, said Luz Torres, Serenity’s grandmother. Due to appointments with shelter staff, Serenity is late to school around once a week, Torres said.

To deal with shelter capacity issues, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in February 2017 a five-year-plan to build 90 new shelter and expand 30 existing facilities, while also phasing out the reliance on commercial hotel rooms to shelter the homeless.

While advocates welcomed improved access to shelters, de Blasio’s goal of reducing the shelter population, which exceeds 60,000 individuals, by only 2,500 people in five years.

“To only see a reduction of 2,500 is very discouraging,” Kliff said. “Better, more accessible shelters is good but that’s not the long-term goal. The long-term goal is to get people out of shelters.”